By Thomas Phillips (Thomas Phillips, 1842) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The equipment is economical enough that many teachers could buy a set for every student. Below is a picture of the equipment I use when I do this as a demonstration. The stuffed gorilla is not absolutely necessary.

Batteries can be substituted for the power supply, the primary-secondary coil set comes with the core and costs less than fifty dollars, and a small galvanometer costs less than ten dollars.

The procedure is extremely simple, and mirrors Faraday’s. In class, we have already observed that electric charge moving in a wire produces a magnetic influence around the wire, which deflects a compass needle. This is known as “Oersted’s Law.” To begin the activity I raise the question, “If moving charge in a wire can influence a magnet, can a magnet make charge move? It seems likely, doesn’t it?”

At this point I’d introduce the apparatus. The galvanometer is a sensitive, uncalibrated meter. If an electric current runs through it, the needle deflects in one direction. If a current runs through in the opposite direction, the needle deflects in the opposite direction. The secondary coil has a lot of turns of fine copper wire. When we connect the galvanometer to the coil, we have made a device that can detect the motion of small amounts of charge within the coil.

I start out by showing when the galvanometer needle doesn’t deflect. Inserting one coil in the other does nothing. Inserting the core may make a small deflection, if your core is slightly magnetic, like mine. Inserting or dropping a small magnet through the coil makes the needle deflect first one way, and then the other. A moving magnetic field can make a current flow!

The real excitement occurs when you energize the coil that is not connected to the galvanometer by running a small electric current through it. Then insert it into the other coil. The galvanometer needle will deflect very noticeably, and even more so when the core is inserted into the energized coil, which becomes an electromagnet. The magnetic field of the moving charge in the energized coil has caused charge in the other coil to move in an electric current. Any change in the magnetic field in the primary coil causes charge to flow in the secondary coil. This phenomenon is known as electromagnetic induction, and its discovery is one of the most consequential discoveries in the history of science. Electric motors, generators, and transformers all depend on it. Our modern technological society owes as much or more to this discovery as any other.

This is a moment for the teacher to act a bit, and show real enthusiasm or feign surprise. The deflection of a tiny needle is neither explosive nor glamorous. You have to be excited or students will not get it. Channel the excitement of Michael Faraday when he made the original discovery after years of work. Proceed to show the effect of changing the current through the energized coil, adding the core, and moving the two coils at different speeds relative to each other. Note that the direction of the galvanometer needle motion is tied to the direction of the motion of the coils relative to each other.

Pretend to be finished. Turn the power supply off, and say “Hey, did you see that! The needle really jumped when I turned the power off.” Turn the power supply on again, and be surprised when the needle jumps in the opposite direction.

Much later, all of these observations were summarized as Faraday’s Law by incorporating the magnetic flux model, but I suggest not jumping right to the equation. Take a few minutes to talk about the excitement Faraday must have felt, and the trepidation at explaining such a mysterious phenomenon. What one model could explain all of these different observations? How would you explain it? Perhaps you will introduce magnetic flux later, but put students in Michael Faraday’s shoes for a few minutes.

Faraday wrote these words much later:

“ALL THIS IS A DREAM. Still examine it by a few experiments. Nothing is too wonderful to be true, if it be consistent with the laws of nature; and in such things as these, experiment is the best test of such consistency.”

Laboratory journal entry #10,040 (19 March 1849); published in The Life and Letters of Faraday (1870) Vol. II, edited by Henry Bence Jones [1], p. 248.

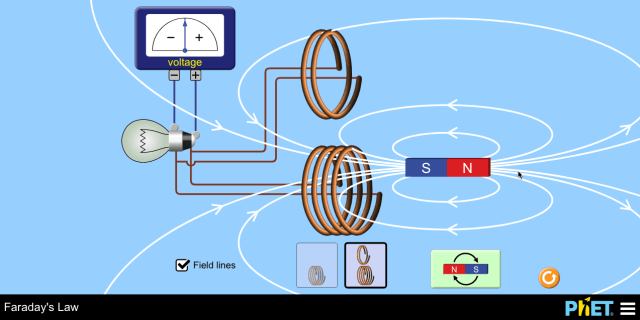

I made a short video of this demonstration, if you’d like to see me perform it (albeit without students). PhET Interactive Simulations has two excellent, free simulations that help students visualize what they have seen in the demonstration. Faraday’s Law (written in HTML5, so it runs on nearly all devices)  and Faraday’s Electromagnetic Lab (which was written in Java, so it will not run on some devices).

and Faraday’s Electromagnetic Lab (which was written in Java, so it will not run on some devices).

Michael Faraday is one of the most important 19th century scientists, yet he was a of paradox. He began his scientific career as a lab assistant and rose to head the Royal Institution. Known for his careful observational experiments, he originated theories that are considered the crowning scientific achievement of his time. Briefly schooled, he knew little about mathematics, yet his ideas led to a mathematical synthesis of the cutting edge physics of his day, the theory of electricity and magnetism. The ring which he used to first observe electromagnetic induction is below:

by Paul Wilkinson, from the Royal Institution of Great Britain

The Electric Life of Michael Faraday by Allan W. Hirshfield is a very readable, relatively short account of his life and work.

You can read Michael Faraday’s original lab entry on the induction ring on this page at the Royal Institution website.

Veritasium made an excellent video in which the host, Derek Muller, visits the Royal Institution and views Faraday’s equipment where he used it.

In AP Physics 2,the relevant College Board Learning Objective is

| 4.E.2.1: The student is able to construct an explanation of the function of a simple electromagnetic device in which an induced emf is produced by a changing magnetic flux through an area defined by a current loop (i.e., a simple microphone or generator) or of the effect on behavior of a device in which an induced emf is produced by a constant magnetic field through a changing area. [SP 6.4] |

And in AP Physics C Electricity and Magnetism:

“b) Students should understand Faraday’s law and Lenz’s law, so they can:

1) Recognize situations in which changing flux through a loop will cause an induced emf or current in the loop.

2) Calculate the magnitude and direction of the induced emf and current in a loop of wire or a conducting bar under the following conditions:

- The magnitude of a related quantity such as magnetic field or area of the loop is changing at a constant rate.

- The magnitude of a related quantity such as magnetic field or area of the loop is a specified non-linear function of time.”